Roswyn Wiltshire explores the challenges of investigating provenance in this article on Roman glass from the collection of Canterbury Museum.

Within the vaults of Canterbury Museum lie well over a hundred ancient glass vessels. Many visitors to the Teece Museum, where a few of these objects are now displayed, have been astounded by the skill with which such fragile vessels were crafted so long ago, and the beautiful condition in which they are preserved. Uncovering their secrets, however, often requires extensive research, challenging the researcher to become a sleuth!

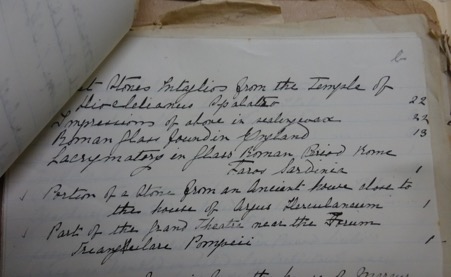

The most well-known portion of Canterbury Museum’s ancient glass collection is known as the Damon Collection, named after the English geologist and conchologist Robert Damon, who actively collected objects between 1873 and 1882. There are, however, a small number of lesser known Roman glass vessels which fall outside the bounds of the Damon collection. One of the reasons these vessels are not as well-known is the dearth of information on their provenance. Trawling through 19th century inventories scrawled in flowing but not terribly legible writing has offered some clues – and sometimes more questions!

Glass from Tharros

Three items (two small flasks and a small jug) were identified in the Museum’s database as coming from Tharros, on Sardinia. One of these flasks bears a diamond-shaped sticker with an identifying number of the first collection it belonged to in Italy before it was sent to Canterbury Museum director Julius von Haast (1822-1887) in an exchange of objects. Antiquities from Tharros are mentioned among new additions to the Museum’s displays in a newspaper article from 1874[1], during von Haast’s time as director. So far so good. Consulting the list that is believed to have been written by von Haast however, I discovered that there were only two glass items noted as coming from Tharros. The first problem was relatively easy to solve. The list read:

Lachrymatory in Glass Roman Period Rome

Taros, Sardinia 1

The ‘Rome’ at the end of the first sentence is probably the provenance for one of the flasks. Perhaps von Haast forgot to number it, and somewhere along the way both flasks (here referred to as lachrymatories which was a common but false identification) began to be recorded as being from Taros (an alternate spelling for Tharros). A more precise document would have probably read:

Lachrymatory in glass, Roman Period: Rome x1

Taros, Sardinia x1

The number of Sardinian glass vessels from Tharros was reduced to just two, as per von Haast’s original list – but the case was not yet closed. The second item from Tharros had been referred to as an amphora in one list, and aryballos in another – were these mistaken references to the same small jug mentioned in the Museum database?[2] I looked again to von Haast’s list for clarification, and found a glass item listed as ‘amphora’, with the Phoenician finds from Tharros.

My examination had proven that the small jug was blown-glass (ie glass shaped by blowing air through a blowpipe into a glob of molten glass). This meant the jug could not be Phoenician, for that technique was only discovered during the 1st century B.C.E[3], long after the Phoenician civilisation had declined. So which piece had von Haast been referring to as a Phoenician amphora?

As it happens, Canterbury Museum does have an amphoriskos of the late 6th – early 5th century B.C.E. This amphoriskos, meaning ‘small amphora’, is a lovely little core-formed vessel, 7.1cm high, with what is known as ‘marvered’ decoration. The hot glass was wrapped around a core, before more coloured strands of glass were added on top. The vessel was then rolled on a flat surface so that the layers merged into an even, decorated surface. The artisan put a lot of effort into this single piece – when it cracked during the manufacture process it was patched up with an extra blob of blue glass. This detail suggests that the artisan felt it still worth selling, rather than tossing it out and starting again.

It dates to a period in which the Phoenicians were active (though their power was waning). It is the correct form, and a very similar example has been found on Tharros[4]. It would not be unreasonable, therefore, to suspect that this is the second piece from Tharros mentioned in the 1874 article.

Unfortunately, where the mislabelled small jug might then come from, is another, and as yet unsolved, mystery.

Glass from England and Rome

A similarly convoluted identification mystery arose with a collection of 11 glass objects labelled as being from England and Rome. Of those, six fragments bear the latter identification, but the only glass object from Rome listed by von Haast is the aforementioned ‘lachrymatory’. Nor does the 1895 Guide to Collections in Canterbury Museum make any mention of glass from Rome[5]. My initial thought was that these may have been much later additions to the collection.

I then noticed an entry of “Roman glass found in England”; thirteen pieces, of which, the 1977-1980 catalogue notes, six are missing. Could the fragments I found labelled as being from ‘Rome’ be those missing pieces, the label erroneously added by someone who saw ‘Roman’ and thought of the place rather than the people? It would be very straightforward to declare these the missing items, if only they could be identified as Romano-British. However, my research indicated that the vivid iridescence of the fragments, in hues of bright pink, bronze and gold, is more typical of glass from the Mediterranean, making it unlikely they are Romano-British.

Downcast, I set about dating the remaining five fragments labelled as being from England. Romano-British glass is so well documented that there are hand-books of forms, listing the areas where they are typically found and how common they are. I was surprised, then, to discover that I simply could not find a match for a beaker from this group; a wonderfully intact piece with a thickened, fire-rounded rim. Eventually, however, I found two like examples in the British Museum collection[6]. Both were from Cyprus.

I re-examined the other ‘English’ pieces. There were two flasks I had been able to date immediately, as I had looked at twelve of the same type from Damon’s Collection – all of which were from Cyprus. Sure enough, they were not depicted in the Romano-British handbooks. The rest were small flask types that occur all over the Roman Empire, and most of the ‘Rome’ fragments were too small to reconstruct a whole vessel from, but one other piece stood out – a flask of emerald green. I’d found a match in the Louvre collection, but that was also of unknown provenance. In the British Museum, however, was yet another – from Salamis, Cyprus[7].

Although it cannot be proved at this stage, I believe that the glass identified as from ‘Rome’ and from ‘England’ is largely, if not entirely, from Cyprus. It was probably gifted – von Haast acquired whole vessels, not fragments, in his exchanges – perhaps by someone from England. Somewhere along the way a miscommunication may have occurred or a mistake was made, leading to the collection being misidentified.

And why so much glass from Cyprus – not only in the Damon Collection but also in these earlier bequests? That, for once, is easy to answer, and this is perhaps some of the best circumstantial evidence for a Cypriote provenance.

At the time that von Haast was setting up Canterbury Museum and Damon was travelling the Levant, Luigi Palma di Cesnola, the American Consul to Cyprus, was conducting excavations on the island. This was the first time ancient glass was uncovered in such quantities, flooding the antiquities market and bringing ancient glass to public attention – even as far away as New Zealand.

Investigating the provenance of the vessels revealed to me both the limitations and potential of such research. The small jug has, for the time being, been shelved as ‘provenance unknown’, but may in future be identified through other means. The amphoriskos, however, has credibly shed its unknown origin. Nevertheless, without provenance we can still learn from these artefacts – the techniques used in ancient times, the materials available, the objects favoured… And from the amphoriskos, with its repair work, we also have a rare glimpse into the effort involved in making such pieces and the value placed on such an object of the distant past.

Roswyn Wiltshire has just completed a Master of Arts in Classics at the University of Canterbury, researching the hitherto unpublished collection of ancient glass in Canterbury Museum. She has worked with the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities since 2017.

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to the staff of Canterbury Museum for their generous support of this research project, and permission to reproduce images of the Roman glass for this article. Thanks also to photographer Matthew Walters, Science Communication and Digital Imaging, UC School of Biological Sciences, for producing such striking images of the glass.

Footnotes:

[1] Author unknown. June 9, 1874. ‘The Museum’ Press, v. XXII.

[2]An aryballos is like a jug in that it is a single-handled vessel for pouring; more properly, however, it used to refer to ceramic Greek vessels, typically with spherical body. An amphora is a two-handled storage vessel; the miniature variety tend to be referred to by the diminutive – amphoriskoi.

[3]The height of Phoenician power was between 1500 and 800 B.C.E.

[4]Barnett, R.D. and Mendleson, C. (eds.). 1987. Tharros: a Catalogue of material in the British Museum from Phoenician and other tombs at Tharros, Sardinia. London: British Museum Publications. pl. 118, 23/5.

[5]Hutton, F.W. 1895. Guide to the Collections in the Canterbury Museum. New Zealand: Lyttelton Times Company.

[6]The examples in the British Museum are from Kourion (1896,0201.299;1896,0201.300). There is another in the Metropolitan Museum, collected by Cesnola from Cyprus (Lightfoot, 2017. Cat. 60).

[7]BM 1881,0901,23.

Fascinating reading – it does make you wonder how many museum pieces might be sitting in public view, mislabeled thanks to some mix-up or some sloppy note-taking a century ago!

I’m curious about the little glass amphora: if it was formed by strands of glass around a core mold, how is it that the surface so smooth?

Thanks Aidan, glad you enjoyed Roswyn’s article. The amphora was made by marvering the glass, so once the strands are wrapped around the core the whole vessel is then rolled on a hard surface to flatten and merge the glass into a consolidated form, which leaves it with the smooth finish you can see in the image.