The development of the UC 150 anniversary exhibition offered a range opportunities to students and staff, including some interesting research challenges. Finn Adams worked as a research technician on the exhibition, and generated some valuable information about various objects featured in Whiria te tangata: Weaving the People Together. In this post, Finn reflects on one particular research journey.

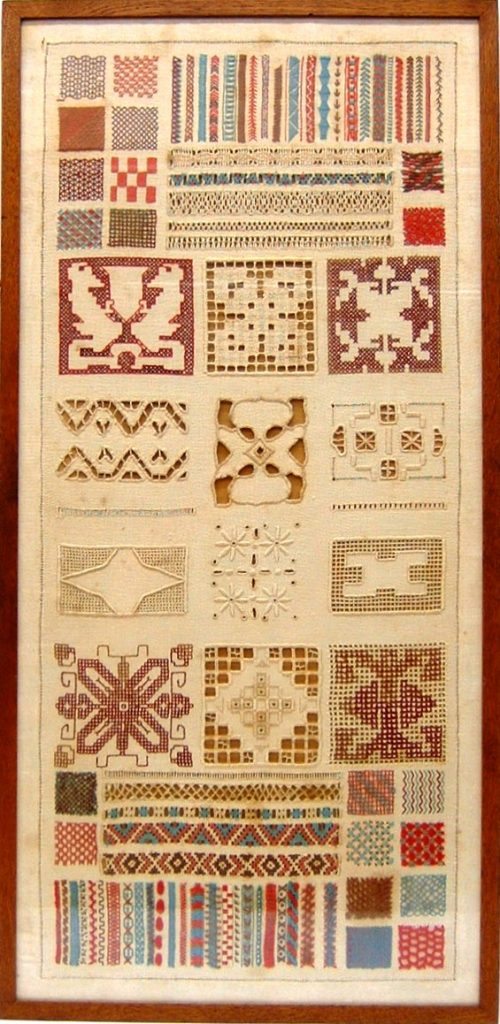

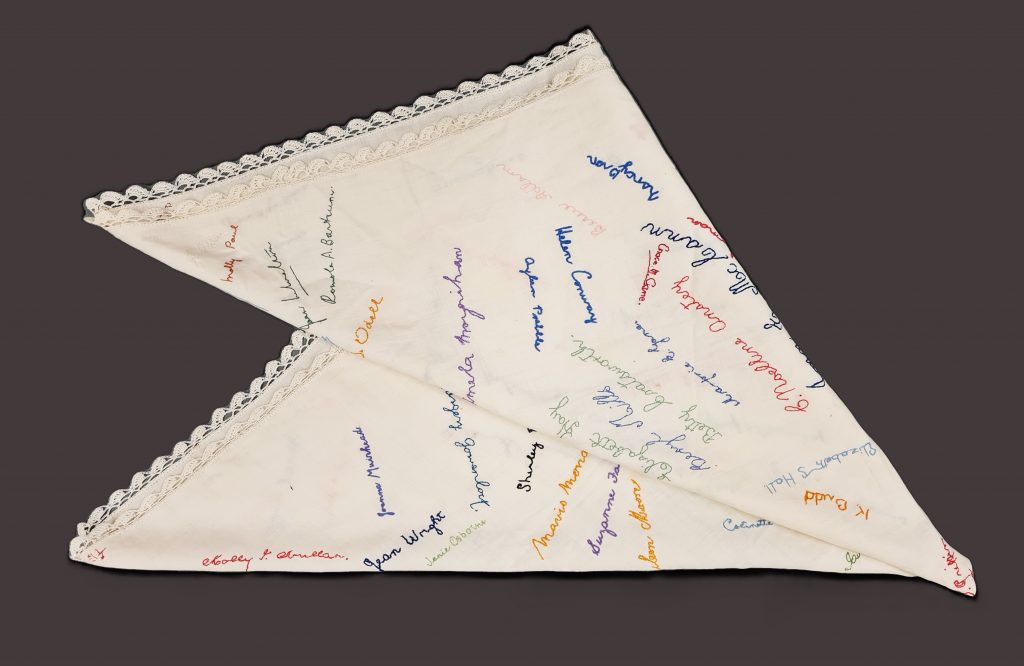

At the beginning of 2023, I was assigned the task of researching objects related to the history of the University of Canterbury (UC) for its 150th anniversary exhibition, currently on display in the Pūmanawa Gallery at the Arts Centre. This was a task that put me into contact with a rather eclectic mix of artefacts, and I researched some interesting items, some of which unfortunately did not make it into the exhibition due to lack of space. One such item was a faded tablecloth emblazoned with many names embroidered in different colours. Although this tablecloth may seem uninteresting at first glance, it proved to be rich in university history and provided a challenging but rewarding research experience.

I say the research was challenging because I was given the tablecloth with almost no information – we were not even certain if it had any links to UC! However, the cloth itself provided a large window to begin research, as written on it were many names that might lead us to an answer. The Curator of the Teece Museum, Terri Elder, provided me with a useful lead, noting that most of the names were female. Thus, she believed, the tablecloth could be related to the women-only hall at UC, Helen Connon Hall.

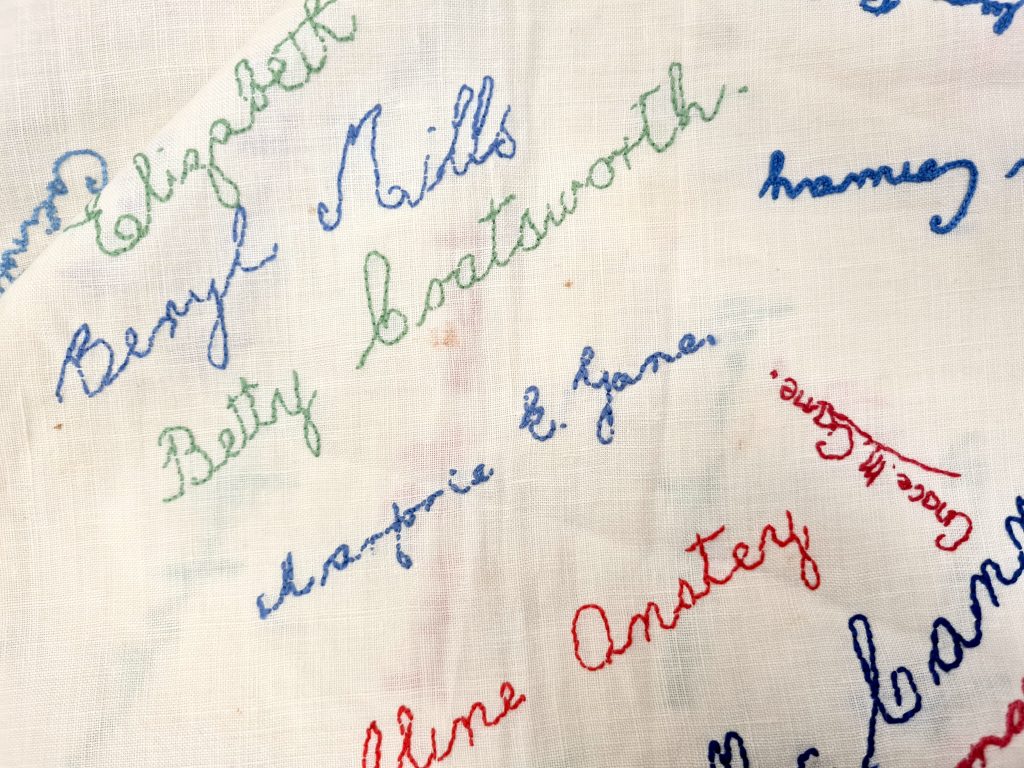

My first challenge was transcribing the names on the cloth. They were all written in cursive, which is infamously difficult to read, especially for a Gen-Z like me. I managed to write out a good number of the names and began trying to identify them. After sifting through old UC Review articles and searching the names on Papers Past, I was able to confirm that some of the women were students at UC in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s. It was not until I got my hands on Marie Peter’s book, Connon Girls: A Study of 20th Century New Zealand Women at University, that I could comfortably confirm that many of the women also went to Connon Hall. The book contained several images that identified the women in the photos, and I found that many of their names were present on the tablecloth.

Having roughly confirmed part of the tablecloth’s story, I was still at a loss as to why it had been made in the first place. I originally thought it might be the names of a specific year group, but as I continued to read Peters’ book, I realised some of the women were at the Hall as early as 1936, and some as late as 1943. As a result, I started to wonder if the cloth was made at a Connon Hall event attended by both current and former residents. For example, Alice Candy, the warden during these years, was known to often host gatherings at the Hall. Furthermore, in 1943 there was a large party for Connon Hall’s 25th anniversary. Perhaps the tablecloth had originated from this party? I thought it may have been made as a sort of guestbook of all the women who had attended the Hall over the years. It was just a matter of finding some small piece of evidence to confirm this. Frustratingly, I was unable to find that elusive evidence and began to believe I had reached a dead end.

Fortunately, whilst I had been researching the cloth, I had continued transcribing more names and researching their individual stories. This eventually led me to find something that completely disproved my first theory! I found two names on the tablecloth of women who attended Connon Hall in 1950. This meant the cloth had been in production during 1950 and thus I began my search for some significant event at the Hall around this time. I realised that 1951 was the year Alice Candy resigned as warden and there was a leaving party held for her. Trawling through Papers Past, I found a Press article which stated that the students of the Hall gave Candy an ‘embroidered table cloth’ at the party. This, I thought, must be it, a cloth signed by students from 1936-1950, all years Candy was warden at the Hall. My theory was crushed once more after consulting Peters’ book, where she also mentions the gift and describes it in more detail as a ‘Chinese embroidered supper cloth’ – surely not the tablecloth I was looking for.

Luckily, looking at sources related to Alice Candy’s retirement led me along the right track. After expanding my search to include later dates, I stumbled upon a Press article which described a gathering in 1954 in honour of Candy. Here I finally found what I had been looking for. The article reported an interview with one of Candy’s former residents at Connon Hall, Nancy Caughley. In this interview, Caughley said Candy had a large tablecloth which she would ask her students to sign. Candy would then embroider over the signatures with whatever colour thread she deemed suitable. Caughley also recalled a time where she read out a name on the cloth to Candy, whom upon hearing the name, decided to unpick it from the cloth! Upon closer inspection, you can see where several names have been unpicked. So, the article informs us that the tablecloth was kept by Candy throughout the 15 years she was at Connon Hall. Given that all the names of her students are not present on the tablecloth, it is likely she asked only her favourites to sign it or rewarded good students with the honour of signing their names. Those who fell out of favour evidently ran the risk of being removed.

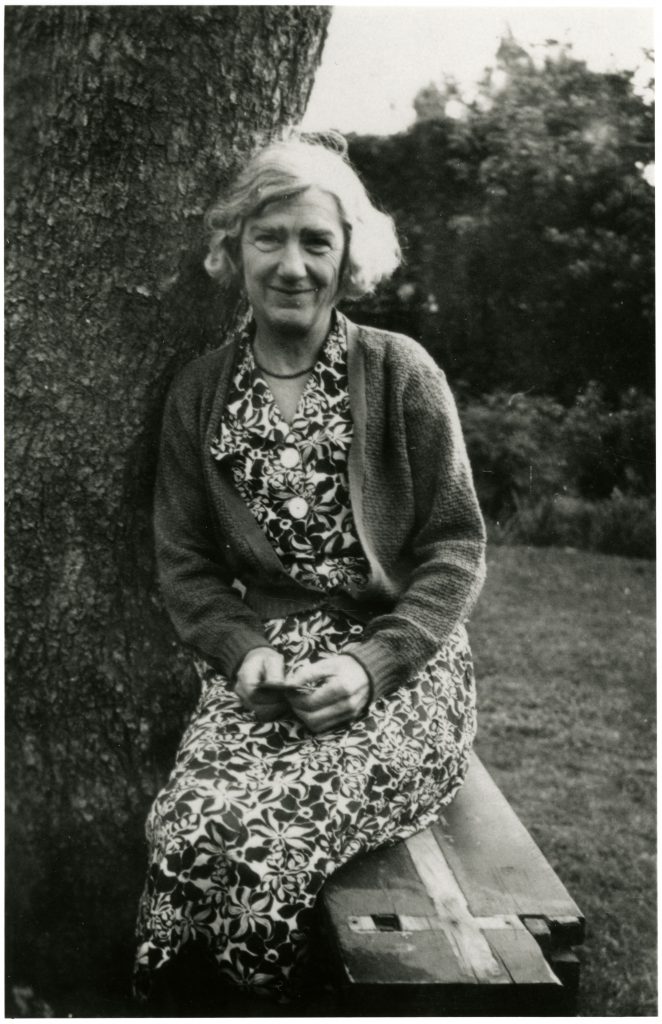

I can now say with certainty that this tablecloth is an item of significance for Connon Hall, which in turn is itself an important part of UC’s history. Connon Hall was the first residential hall for female students established by a university college in the country. In operation between 1918 to 1974, the hall was named after one of New Zealand’s most important university graduates, Helen Connon. Among her many achievements, Connon is most noted for being the first woman in the British Empire to receive a postgraduate degree, receiving a Master of Arts with first-class honours in 1881. The Hall housed many notable women during its time, including the maker of this tablecloth, Alice Candy. Before becoming the Hall’s warden, Candy had graduated from Canterbury College and was appointed as a lecturer in History in 1921. She was well-known for her enthusiastic lecturing and left her mark on the documentation of the University’s history by collaborating with James Hight in the writing of A Short History of Canterbury College, a book I can personally say is still useful today. According to Peters, Candy excelled in her role as warden of Connon Hall, with her former residents having an overwhelmingly positive opinion towards her. By her retirement Candy had a distinctive influence on the Hall and the University. Today, she is commemorated at the University by the naming of the ‘Alice Candy’ building.

Although not as well-known as Candy or Connon, many women whose names were embroidered onto the cloth demonstrated the same excellence in their lives.[1] Grace M. Gane is one of the names that I was fortunately able to uncover more fully. She attended Connon Hall for at least one year in 1941. After studying at the Teacher’s College, Gane somehow made her way into speech therapy, becoming Wanganui’s first speech therapist. She had a very successful career, serving as the editor of the New Zealand Speech Therapists Association Journal and publishing an article in the International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders in 1968. According to the New Zealand Speech-Language Therapy Association she is a founding figure for our country’s practice of speech-language therapy.

Another interesting student is Eila G. Simpson, who was also at Connon Hall in 1941 and received her Master of Arts sometime in the early 1940’s. Simpson was eventually seconded to the Department of External Affairs at New Zealand House in London. In this role she answered a range of questions from curious Brits about New Zealand, educating the British populace about our country. She reputedly answered questions such as: how to pronounce Māori words; if you could marry your wife’s sister; if you could transport your husband’s corpse to New Zealand; or how much Stewart Island was valued at! Unfortunately, we do not know any more of Eila’s story.

Lastly, an odd story comes from Doris Adams who attended the Hall in 1936 and became a teacher. A Press article I found reports that on her way to Kirwee School one morning in 1939, she parked her small Sedan on some train tracks and was hit by a train. She miraculously escaped with only a slight cut to her head. In 1946 she went off to Bengal to work as a missionary, which caused me to wonder if the two events were connected.

The tablecloth turned out to have a wealth of university history tied to it through its connection to Connon Hall, Alice Candy, and some very interesting students. The charming story of the tablecloth’s origins demonstrate the heart in university life. Candy certainly cared about her students enough to create a rather sentimental item during her time at the Hall. This contrasts with the rather cold and distant stereotypes often given to university figures, although Candy’s proclivity to erase names from the tablecloth perhaps undermine this statement a tad. Additionally, for me, the tablecloth provided a tough but very satisfying research project, which hopefully shows the reader not to settle on probable conclusions if there is still some more digging to be done.

Finbar Adams works part-time at the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities as a Gallery Host and Researcher. He recently graduated from the University of Canterbury with a Master of Arts in History. Finn has found working at the Teece has been a valuable experience, particularly as he has been able to assist in the research and installation process of the University of Canterbury’s 150th anniversary exhibition.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to the knowledgeable staff of the Macmillan Brown Library at the University of Canterbury for their help finding sources and images for this article.

Footnotes:

[1] I should note many names on the cloth are still yet to be identified. The students I was able to identify often had little information about them recorded, meaning many an interesting career and life have not been revealed.

Bibliography:

Peters, Marie. Connon Girls: A Study of 20th-Century New Zealand Women at University. Christchurch, New Zealand: Helen Connon Hall History Project Committee, 2017.

“CURRENT NOTES”, Press, vol. XC, no. 27329, 21 April 1954, Christchurch, New Zealand, 1954, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19540421.2.4.9, 2.

Biography – Alice Candy:

Alice Muriel Flora Candy was born 9 July 1888 in Oxford, New Zealand. She is a well-known New Zealand historian, academic, and teacher. She graduated from Canterbury College with her Bachelor of Arts in in 1910 and acquired a Master of Arts in 1911 with Honours in Political Science. From 1912 until 1920 she taught at a variety of schools around New Zealand.

At the end of 1920 she was appointed a lecturer in history at Canterbury College as the junior and sole colleague of James Hight. While as a lecturer she became well-liked for her enthusiastic teaching style, she seemed to be a natural teacher and so does not have many published works. She did, however, co-write A Short History of Canterbury College along with Hight in 1929. This book as an extremely valuable piece for the early history of the Canterbury College and the first of two University of Canterbury history books to date.

Whilst still lecturing at Canterbury College Candy was appointed the resident warden of Helen Connon Hall in 1935. From 1936 to 1951 Candy remained the warden at the hall and was viewed very favourably by most of the hall’s residents. She retired from her academic position at Canterbury College in 1948 and in 1951 she resigned as warden of the hall. She retired to her home in Redcliffs Christchurch, where many of her former students and residents would be encouraged to visit her. She passed away in 1977 at the age of eighty-eight.