In 2017, Roswyn Wiltshire completed a PACE internship with the Teece Museum, transcribing a travel diary which belonged to Miss Marion Steven. The process of reading, translating, interpreting and researching the diary entries revealed some fascinating new angles to Marion’s story. Here, Roswyn contemplates whether the story of Marion’s journey might also shed light on the challenges faced by female academics post World War II.

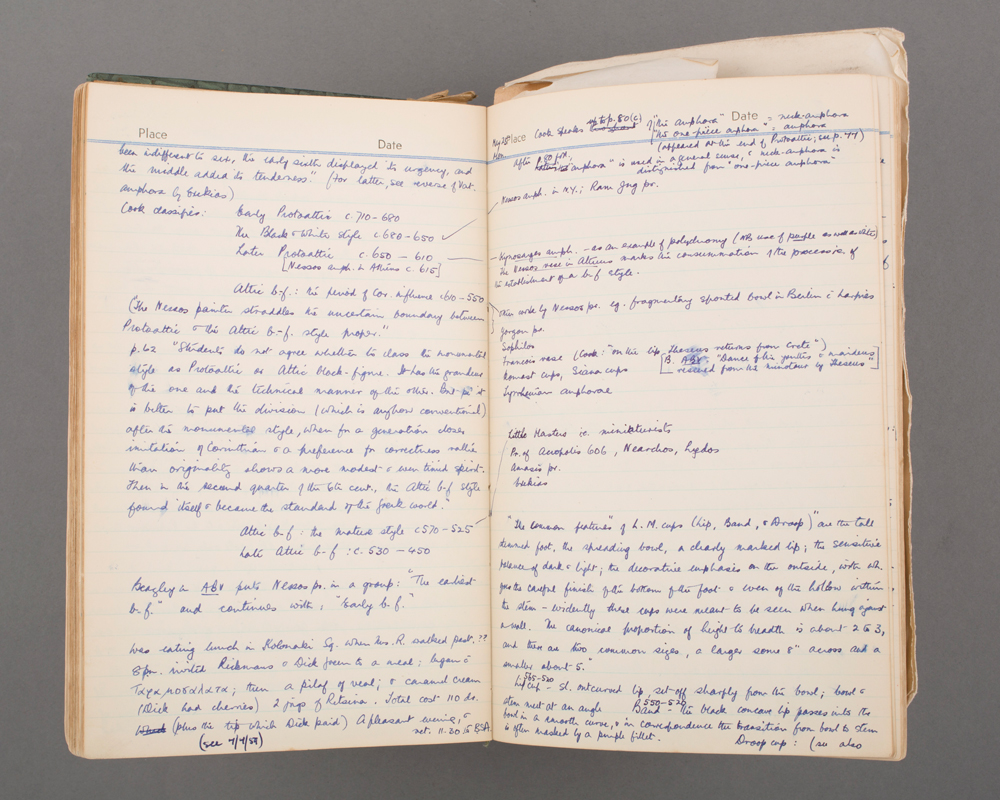

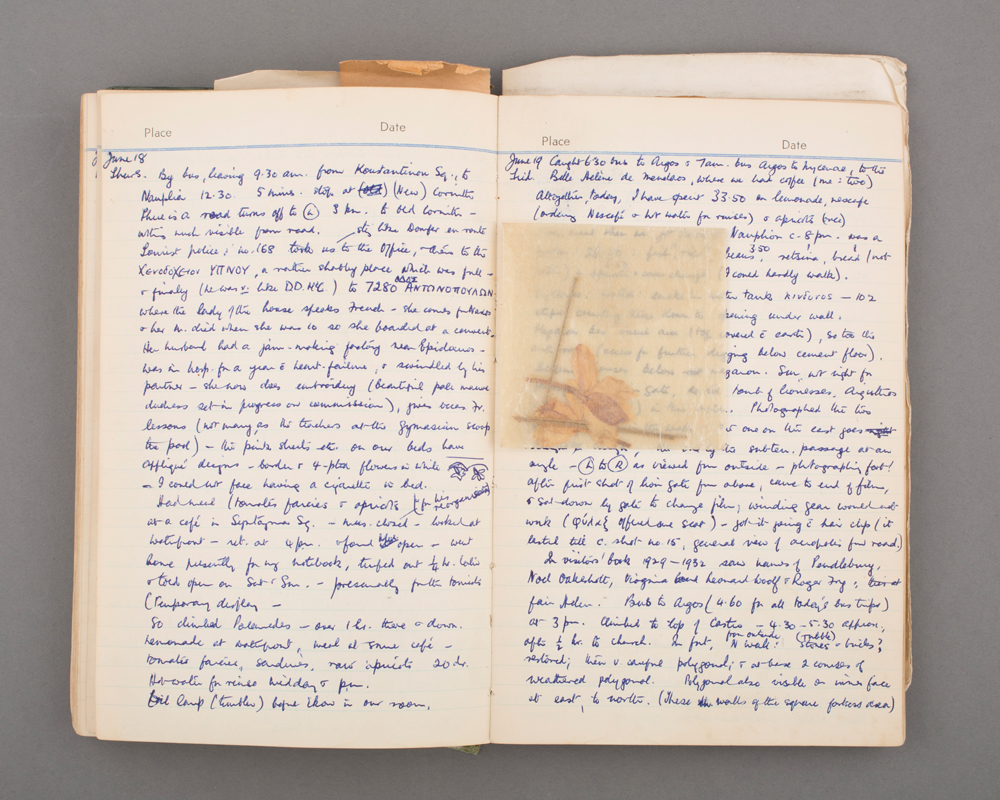

Since the donation to the Teece Museum of Marion Steven’s travel diary and the extensive oral history project undertaken by Natalie Looyer, we have begun to learn more about the vivid character of the James Logie Memorial Collection’s founder, Miss Marion Steven. Marion travelled extensively during her career, visiting colleagues, museums, and archaeological sites. Before embarking on one such trip at the end of 1958 she was gifted a journal in which she recorded notes of meetings, lectures, artefacts, performances of ancient Greek tragedies, and on-going excavations. When transcribing the diary I also undertook research into the context of what I was reading. One major thread that emerged in this process was the situation of women in academia, and specifically the disciplines of classics and classical archaeology, during the post-World War II period.

Miss Steven’s legacy is emerging as an inspiration to young classicists – a woman who resolutely went her own way and rose to become Reader – Associate Professor in today’s terms – at a time when the academic world was dominated by men. During the span of her career, women were always less than ten percent of the teaching staff at the University of Canterbury. This imbalance was an ordinary part of life for Marion, and it can be difficult to discover if she had any particular views on the situation faced by her and her female colleagues. By comparison with pioneering women of the field we can discover the range of stances on feminism, but in Marion’s own diary it is difficult to identify any real hints of her opinion.

One of the challenges women academics who worked alongside their husbands encountered was that they too easily fell into obscurity. When transcribing Marion’s diary, for example, it was difficult to find anything about the ‘Mrs Wace’ mentioned who showed Marion’s colleague, James Stewart, photos of the recently excavated shaft graves at Mycenae[1]. Marion elsewhere had referred to the Wace’s excavations, but the report on those excavations from Alan John Bayard Wace only mentions “Mrs. Alan Wace” among “other members of the excavation who undertook various parts of the work”. Miss Elizabeth Wace, his daughter, who would go on to be Director of the British School in Athens, was also “actively present throughout”[2]. “Mrs. Alan Wace” was in fact Helen Pence, an archaeologist in her own right who had studied in Rome. Learning about such women I became less surprised by Marion’s insistence on being addressed as Miss Steven after her marriage. Although Marion and her husband were not in the same field, keeping an identity separate from the traditional role of wife was no doubt important.

When learning about the achievements of women like Marion, striding forth in careers and environments dominated by men, we may well ask ourselves “were they feminist?” To succeed in a man’s world does not necessarily require challenging the established hierarchy. From the early days of archaeology there were women both stridently feminist and fervently anti-suffrage, with many shades between. On the one hand, Gertrude Bell, an English archaeologist who also worked for British Intelligence during World War 1, was fervently anti-suffrage. The American archaeologist Harriet Boyd Hawes had doubts about suffrage, and felt “that a woman’s chief concern should be with the arts of living and homemaking” and the Danish academic Lis Jacobsen expressed similar sentiments very publicly, seeing herself as an exception. In contrast, the Egyptologist Margaret Murray was the first woman in the United Kingdom to be appointed as a lecturer in archaeology, and she was also a suffragette in the militant Women’s Social and Political Union. Also at the other end of the spectrum, Gertrude Caton-Thompson, whose work focused on prehistoric Egypt, remarked that “since the early ’30s my feminist allegiance led me to have a woman doctor”[3].

From the character that comes through in Marion’s diary, I believe that this quiet feminism, seeking to give women opportunities wherever possible, was the kind that would have appealed to her. She had herself been denied her first career opportunity in medical science by gender discrimination and was aware of the difficulties women faced[4]. However, studies interviewing women archaeologists who were contemporaries of Marion found that their subjects remembered little or no discrimination, even when statistics suggested otherwise[5]. To the successful, it is not always clear how one can fail through any fault but one’s own.

Marion’s travel diary did not focus on this matter. She was primarily concerned with making notes for use in teaching. The diary also served to keep track of expenses, with accounts of travel and food costs. Personal interactions are often reported in a single, heavily abbreviated sentence. Everything recorded was either useful or important to her – and thus, however brief, the very fact that she chose to record a particular snatch of conversation is always significant.

One such passage is in her account of a visit to Sir John Beazley in Oxford. Beazley was a renowned classicist, and Marion’s connection to him had a significant impact on the prominence of the Logie Collection. Beazley even bestowed the name ‘Logie Painter’ on an Attic vase painter who created the ‘Logie Cup’ from the Collection, and another kylix in the Louvre. But in this particular meeting the subject of their discussion – the Berlin Painter – is suddenly followed by a remark from Marie Beazley.

“ – Lady B[eazley], when they were working in B[ritish] museum before war – [said that it was the] ‘only time she felt free’”[6].

Marie Beazley is typically a footnote to her husband, without an easily traceable record of her own career. Yet Marion implies that Marie was working at the British Museum alongside her husband, and that this gave her a sense of freedom unprecedented in her life. It is one of the very few occasions that Marion directly quoted anyone in her diary, and gives us a possible hint of where her convictions lay.

I believe Marion was very much aware of how difficult it was for most women to succeed in academic careers as she had done. The scale of gender inequality in academia may have never stood out as much to Marion as it does to us, for it was, lamentably, normal. As for what she did in response, Marion was not a flamboyant activist personality. Perhaps more importantly, however, she was fully invested in supporting her students. Through the Collection she established and through her example as a role model, she continues to be a guiding and inspiring presence to new generations of classicists.

Roswyn Wiltshire has worked as a gallery host at the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities since 2017. She has just completed a Master of Arts in Classics at the University of Canterbury.

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to the Steven Family for their continued support of the Logie Collection, and permission to reproduce images for this article.

[1] MKS Travel Diary, February 27th 1959. Page 62. Logie Collection Archives, uncatalogued.

[2] Wace A.J.B. 1950. ‘Excavations at Mycenae, 1939’. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 45, pp. 203-228.

[3] Bolger, 1994, 48 in Claassen, C. ed. 1994. Women in Archaeology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Jørgensen, 1998,219-220; Champion, 1998, 193 in Diaz-Andreu, M. and Stig Sørensen, M. eds. 1998. Excavating Women: A history of women in European archaeology. London and New York: Routledge.

[4] Marion received a scholarship in pathology at Middlesex hospital London; she had applied under M.K. Steven. When she arrived, it was withdrawn due to there being ‘no facilities for women’. Holcroft, A. ‘Obituary: Marion Kerr Steven’, in Chronicle v. 34 no. 4 (1999): 8-9.

[5] White, Marrinan, and Davis, 1994; Kästner, Maier, and Shülke, 1998.

[6] MKS Travel Diary, January 8th 1959. Page 35. Logie Collection archives, uncatalogued.

That’s interesting as when I knew/was taught by Miss Steven back in the early 70’s I’d understood she actually wanted to do Classics from the word go but had done the medical degree to please her family so they would not have to worry about her. She never mentioned any obstruction to her medical path but we only ever talked about it briefly once when she showed me where the heart of a mummy was in an Xray.