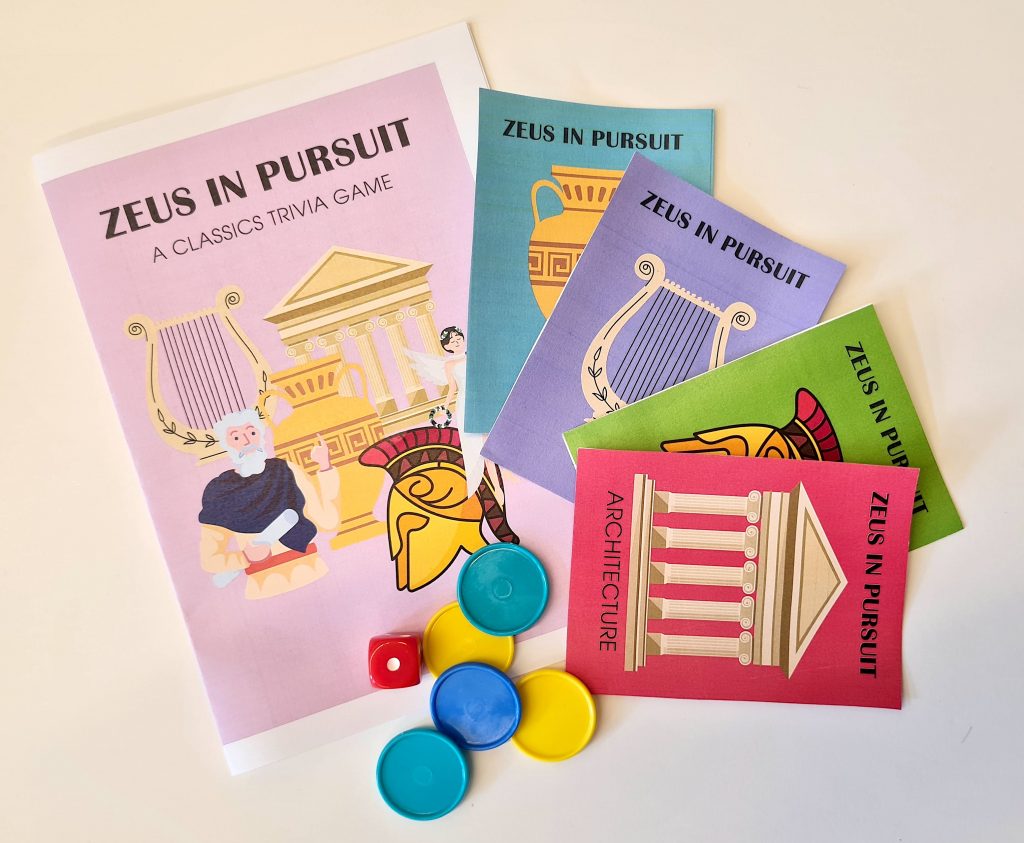

Did you know that a growing percentage of secondary school students get their primary introduction to the ancient world through games? The team at the Teece decided to take advantage of that by expanding the range of board games we offer to students and teachers as part of our education outreach services. Realising that this was the perfect intersection of her academic interests, 2024 PACE intern Isabella Breese agreed to tackle a project aimed at developing a new gaming resource, drawing on her knowledge of classics, gaming, film, and pop culture. In this post, Isabella discusses the research and development involved in creating her game ‘Zeus in Pursuit’.

The beginning

In the second semester of 2024 I began the PACE (professional and community engagement) programme at UC. This course connects students to organisations in the community for internships related to their field of study. As a Classics major, I was placed with the Teece Museum to learn more about how Classics as a discipline is used in the workplace.

During my internship here I worked on a project that would assist in the teaching and learning of Classics and classical reception in the classroom. Classical reception is the study of how the ancient world is received and portrayed by the modern world. To accomplish this, we decided to create a trivia card game that would feature Classics trivia, and contrast it with references to Classics in pop culture. Our aim was to create an engaging resource that would reinforce content learned in the classroom and develop learning through fun. This in turn will allow the students to create deeper connections to the information.

The first order of business was to look into the current New Zealand Curriculum for Classics and see how the project could work conjunction with its requirements. The learning outcomes that aligned with our aims were:

- Examining the significance of features of works of art

- Analysing the impact of a significant historical figure

- Understanding the relationship between aspects of the classical world and other cultures

- Understanding lasting influences of the classical world on other cultures across time

Overall, our intent was that the game should be a small resource which could contribute to these learning outcomes in one element or another, and assist teachers in supporting and reinforcing the information they are teaching in the classroom.

Researching and Development

To gain inspiration, I looked into already existing Classics games to understand their formats, design, and content. This was helpful and allowed us to come up with a few concepts. After a bit of deliberation, we chose the trivia board game format. This is because we felt trivia games would work best with our learning goals. They can promote fact memorisation, the competition generates excitement and interest in learning the subject, and even if a player does not know the answer, they can learn new facts through playing. Additionally, a trivia game only requires simple rules and intuitive content design that makes it achievable for a first-time game designer.

The next task was to generate content. I created a list of pop culture with references to Classics and looked into my own notes from previous university courses. The research ended up being an ongoing portion of the project as I was constantly looking for content when creating each new card (there are fifty-five in total).

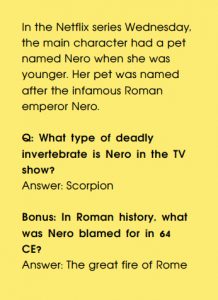

We decided to split the questions in the game into two types: modern and ancient. This was to align with our goal for a game that presented ideas on classical reception, because the students can both learn about ancient Classics and see how it is represented in modern media. For the modern section, the game looks at classical references within video games, comics, books, films, and songs. As a result, students can relate to the information closely, and reinforce their knowledge gained from class. Additionally, including questions centred on pop culture which students are more likely to be familiar with could increase engagement in the game and their chance of learning something new. A few examples of the media we used are Coraline, God of War, Assassins Creed Odyssey, the D&D monster manual, and Disney’s Hercules. All of these, whether it is obvious or not, have a connection to ancient Greek or Roman culture.

We also decided to further split the game into five main categories: myth, architecture, music, people, and art. All of the questions in both the modern and ancient sections fit within these areas of study. For example, an ancient architecture card may ask about Roman aqueducts, and the modern architecture card may ask about the neoclassical architectural elements within a scene in The Hunger Games film. Or the ancient myth card may ask about Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, while the modern card questions players about Charon’s job in the video game Spiritfarer.

Game structure

The card structure works as follows: Each player takes a turn at reading out a game card. There is a blurb at the top of the card that provides context for the questions. Below this is the main question, with the answer given underneath. This is followed a bonus question with its answer also given underneath. The goal of the game is to answer as many questions correctly as you can and win 6 tokens first. A token can be won either by answering a question correctly before anyone else, by following the instructions on a wild card, or (and here’s the fun part!) through stealing a token from another player. The steal mechanic works by answering the bonus question from any card. The player who answers correctly is then given the option to choose a new token from the pile or to steal one from another player.

Issues

Now, when creating any new project, problems are bound to arise. Luckily the issues we ran into were very small. For example, throughout the process of content creation and design, the game passively changed from a board game into a card game. We realised that a board, although in the initial idea, wasn’t really necessary to the structure we were developing. This project also involved a great deal of editing and testing to make sure the content made sense, was accurate, and was doing what we needed it to do. The test games in particular were really cool as they allowed for real-time feedback from players and immediately highlighted any areas that needed more work.

For example, we found it was important to address the clarification of questions and content, as the wording could get confusing at times. Also, the amount of information held on a specific card and the difficulty level of the questions needed to be adjusted. Additionally, pronouncing Latin and Greek words was a subject of struggle for a lot of people. So, to fix this, we added a cheat sheet of phonetic pronunciations in the rule book that can be easily accessed if needed.

Another issue we came across was that there was some difficulty around how to distinguish the content in each category. A lot of pop culture concentrates almost solely on myth, rather than architecture or famous figures, and there was a lot of cross over between categories. We started off with five categories – art, architecture, people, myth, and religion. However, early on we realised that the religion cards and myth cards had no specific defining traits of their own. Initially we removed the religion cards and cut the game down to four categories. However, near the end of the project when we found we were ahead of schedule we were able to add one last category – music.

Summary

To recap, the goal of this project was to create a classical reception themed trivia game that can be used in the classroom. As it aligns with the NZ curriculum, it should allow for the students to strengthen the knowledge they learn in class by relating it back to everyday media.

What surprised me personally about this project is just how interesting it was to create a learning resource that explores both ancient classical information and classical occurrences in pop culture such as video games and movies. To any teacher that may be interested in creating a game as a teaching resource such as this, I highly recommend finding a connection to pop culture in at least one aspect to really engage and connect with the younger audiences.

Isabella Breese recently obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in Classics and a minor in Cinema Studies. She has just completed a PACE495 internship with the Teece Museum, and is finishing up her honours year at the University of Canterbury.