The daily lives of the ancient Greeks and Romans can be difficult to relate to, but in some respects the Classical world was very much like our own. Teece Museum Gallery Host and UC graduate Brylea Hollinshead considers our differences and similarities in this survey of fun and games in the ancient world.

With their majestic temples, great philosophers, and formidable armies, the ancient Greeks and Romans are often seen as a sober and serious bunch, elevated in the popular imagination to the heights of the gods they worshipped. You might think that all of their time was occupied by lofty matters like the development of the arts, rational study, and military training. However, this viewpoint overlooks the playfulness which was present in the everyday lives of Greek and Roman men, women, and children. This article will bring the ancients back down to earth by exploring fun, games, and silly antics in the Greek and Roman worlds through artefacts in the UC Teece Museum and Logie Collection. We will consider the relationship between gender and play, and note how ancient attitudes differ from our own. Yet unearthing our commonly shared forms of fun – from children’s toys to drinking games – will reveal that we are perhaps more like the ancients than we think.

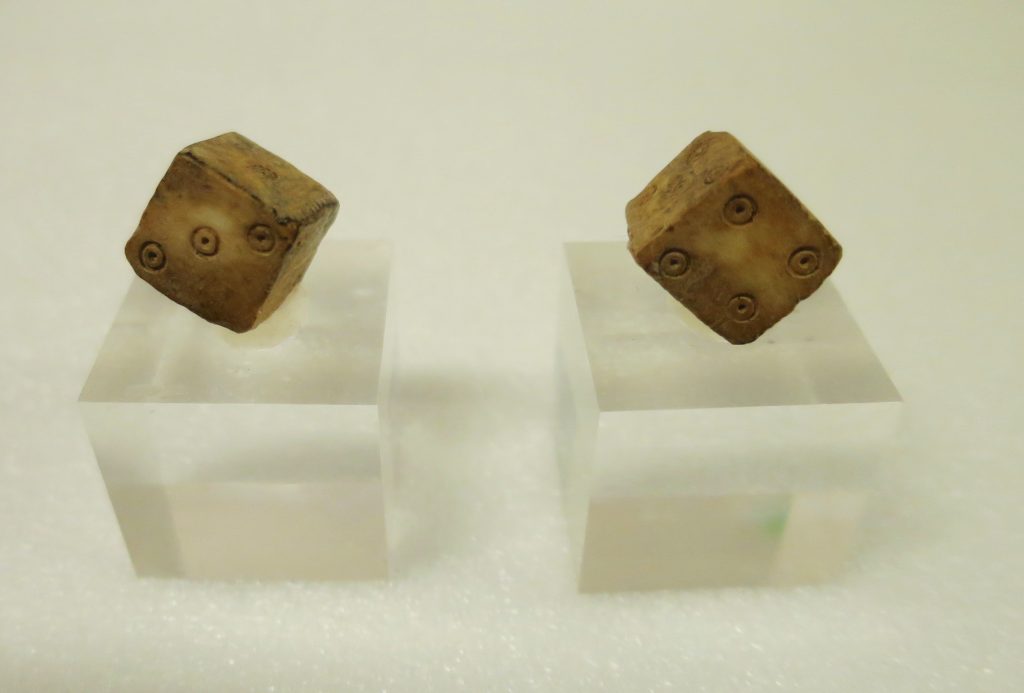

Greek and Roman children, just like kids today, entertained themselves with toys and games in their free time. Animal models, like this terracotta figurine of a horse and rider (JLMC 35.55) currently displayed in the Teece, made popular toys. One can imagine a young child might have cherished this little figurine over two millennia ago. Dice too, are not a modern invention, but were a popular game in the ancient world. The Greek playwright Sophocles credits the hero Palamedes with their invention during the Trojan war. [1] However, archaeological excavations place their origins even earlier – six-sided dice much like our modern-day equivalent have been discovered in Egyptian tombs dating from as far back as 2000 BCE. [2] The Teece houses this wonderful example of a pair of bone dice from the Roman period (DG 277), which bear remarkable resemblance to the dice you might find in a store today. Board games like latrunculi and tabula (similar to chess and backgammon) were also common, as were knucklebones made from the bones of animals like sheep and goats (hence the name!), and balls made from inflated pigs’ bladders.

Toys could also serve the function of reinforcing gender expectations and preparing children for their future social roles. In the ancient world, male citizens were expected to participate in society’s public sphere by becoming, for instance, politicians, soldiers, or labourers. A woman’s role, by contrast, was primarily to become a wife, bear children, and manage the household. Therefore, young boys often played with toys like tools, and girls with dolls. The Greek philosopher Plato drew this link between play and education, stating “if a boy is to be a good farmer or a good builder, he should play at building toy houses or farming . . . One should see games as a means of directing children’s tastes and inclinations to the role they will fulfill as adults”. [3] The separation of girls’ and boys’ toys, though still present today, is being challenged as patriarchal ideals break down and both genders gain more opportunities.

Merriment and games were not restricted to childhood – the Greeks and Romans retained their sense of play into adult life. Sports and athletics, for instance, were fundamental aspects of ancient society. The Greek cultural appreciation of athleticism culminated at the Olympic games, a tradition which has retained its popularity into the modern day. First held at Olympia in 776 BCE, adult male citizens competed in wrestling, long jump, running races, shot put, and discus. The Romans, too, enjoyed sporting contests, with chariot racing and gladiator combat being particularly popular games. In Rome these grand spectacles were held in a giant arena called the colosseum, and captured the interest of all areas of society, from poor workers to Roman emperors like Nero, who bet large sums on their outcomes. The emperor Commodus himself even competed as a gladiator!

The evenings held the opportunity for a different kind of play. The Greek symposium (a term which is now, ironically, used in English to denote a formal professional conference) was a drinking party for elite males renowned for its boisterous fun, games, and revelry. Symposia involved the consumption of food and alcohol, and entertainment such as music, poetry, and dance. The kylix, a drinking cup for wine, often became part of the fun itself. For instance, the exterior of some kylikes were painted with a feature which may seem odd to modern viewers at first glance: a pair of eyes.

A striking example of this is shown by the Teece Museum’s “Logie Cup” (JLMC 56.58). It is thought by scholars that these eye-cups were used as a kind of mask. During the symposium, a symposiast would raise his wine-filled kylix to his lips, covering his face. The cup’s painted eyes would stare out at his companions, while its handles and circular foot would become ears and a bulbous nose or gaping mouth. Undoubtedly, the amusement aroused by this trick would increase alongside the revelers’ levels of intoxication.

Symposiasts also used their cups to play kottabos. This ancient equivalent of a modern-day drinking game involved the partygoer flinging the dregs of the wine from his cup towards a designated target. A successful toss won the symposiast prizes and was seen to bring good fortune in love. A self-referential kylix in the Logie Collection shows a man reclining on a couch at a symposium holding a kylix (JLMC 17.53). After a few sips, the contents of his cup might have gone flying!

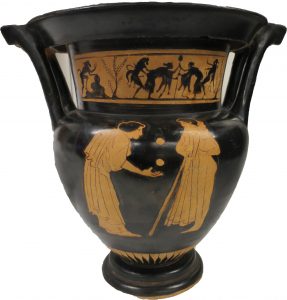

Women in ancient Greece and Rome did not enjoy the same freedoms as men, and the majority of them were prohibited from joining in the fun at athletic contests or wild drinking parties. Little first-hand information exists on the private lives of ordinary women, who spent much of their time inside the household. However, they undoubtedly found their own ways of making fun, even while confined to their homes. This column-krater (used for mixing wine and water at symposia), for instance, shows two women juggling in a fairly rare artistic depiction of women at play (DG 305).

The scene on the neck of the vase references a wilder and more disinhibited realm of play involving women. It depicts the mythological followers of Dionysus (or Bacchus), the god of wine and madness, engaged in an orgiastic scene of debauchery. The satyrs, who were conceived as silly, buffoonish, and lustful creatures, advance on their female companions, the maenads (whose name translates to raving ones). Some of the maenads playfully fend off the satyrs with thyrsi, or pinecone topped staffs. Though these characters were creations of myth, the god of madness inspired worship from real women in antiquity, who joined groups like the Greek Dionysian and Roman Bacchic mystery cults. Inspired by the god, initiates of these secretive sects took part in ecstatic rituals including intoxication, trance-inducing song and dance, sacrifices, and sexual activity. Such frenzied Dionysian “play” offered a kind of fun and freedom to marginalised members of society like women, which they might otherwise have lacked in their everyday lives.

Fun and games played an important part in the everyday lives of ancient men, women, and children. Alongside work, study, and civic duty, Greeks and Romans played with toys and challenged each other in board games, spectated and competed in sporting contests, and engaged in Dionysian revelry through drinking parties and mystery cults. Recognising this lively, all-too-human element of ancient cultures connects us to the past not only through our most serious endeavours, but also through our ability to have fun.

Brylea Hollinshead has just completed a Bachelor of Arts in Classics and Philosophy at the University of Canterbury, with a particular research interest in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy. She has been working as a gallery host for Teece Museum since 2017.

Footnotes:

[1] Sophocles, Palamedes fragment, 479 R trans Kidd, Stephen E. “How to Gamble in Greek: The Meaning of Kubeia.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 137 (2017): 119-1

[2] Glimne, Dan. “Dice”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 Feb. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/dice. Accessed 14 April 2021.

[3] Plato. Laws 1.643b-c, trans D’Angour, Armand. “Plato and play: Taking education seriously in ancient Greece.” American Journal of Play 5.3 (2013): 293-307. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1016076.pdf Accessed 14 April 2021.

The exhibit on fun and games in the ancient world sounds intriguing! Historical entertainment is always a fascinating subject. For those setting goals, this article on SMART goals is very useful: S.M.A.R.T. Goals: Organized Goals, Directed Success.