UC Classics graduate Emily Rosevear explores the history of the ancient world through an examination of a special text in the University of Canterbury Library Rare Books Collection, which is known as the Canterbury Sallust. Produced around 1465-70 CE, the Sallust manuscript is a rare edition of Bellum Jugurthinum by the Roman author Gaius Sallustius Crispus.

The ancient Greeks and Romans came into contact with a wide variety of people across Europe, Asia and North Africa through trade, migration and war. As they expanded their horizons, they developed a fascination with the world around them and the lands beyond their cities. Their interest was strongly influenced by significant historical and political events, including the campaigns of Alexander the Great and the eastward expansion of the Greek world in the fourth century BCE, as well as the consolidation of the Roman Empire under Augustus in the first century CE. These events promoted further territorial expansion and led to an increasing awareness of previously unknown regions.[1]

Ancient Greek and Roman literary works tend to focus on inhabited lands which were thought to be suitable for settlement or offered potential resources.[2] With their interests so closely related to people and conquest, ancient authors often combined elements of we might now view as different disciplines – history, geography, and ethnography – when writing about new places or peoples. For example, well known today are the works of the Greek historian Herodotus (c.484–c.425 BCE) who used geography to frame his narrative by including in his Histories descriptions of the regions under Persian control such as Egypt, India and Scythia. This combination of historical and geographical descriptions became an important feature of later works of the period, including those by authors such as Thucydides, Polybius, and Sallust.[3] The work of Sallust (86–c. 35 BCE) is of particular interest to us, as the University of Canterbury holds a rare early copy of one of his manuscripts.

The Work of Sallust

Contained within the UC Library Rare Books Collection is a copy of Sallust’s work Bellum Jugurthinum. The text is an account of the conflict that erupted in North Africa towards the end of the second century BCE when Jugurtha (c. 160–104 BCE) usurped the throne of Numidia after the death of its pro-Roman king. This work was completed in approximately 40 BCE by Gaius Sallustius Crispus, (or ‘Sallust’ as he is known), who was a retired Roman senator. His work is centred around war and military conquest, with three chapters devoted to the land and people of North Africa. By emphasising the relationship between the physical features of the place and the character of its people who are described as rough, hardy and untamed, he is perhaps alluding to a clash between the civilisation of Rome and the perceived barbarism of the Numidian kingdom where the war takes place.[4]

Fortunately for us, Sallust’s work has survived through to the modern day because copies of his manuscript were read and published across Europe in the centuries following its original publication, thereby preserving his work. This monograph and a slightly earlier one (Bellum Catilinae, completed c. 42 BCE), also by Sallust, are among the earliest historical texts written in Latin that have survived in their entirety from antiquity.[5]

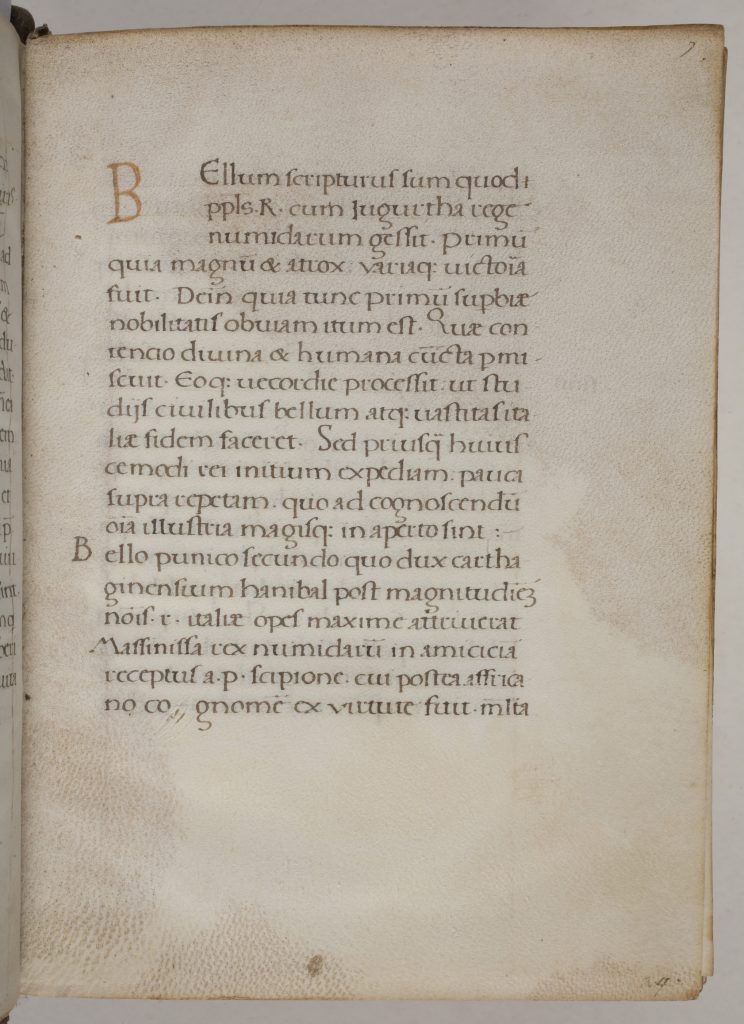

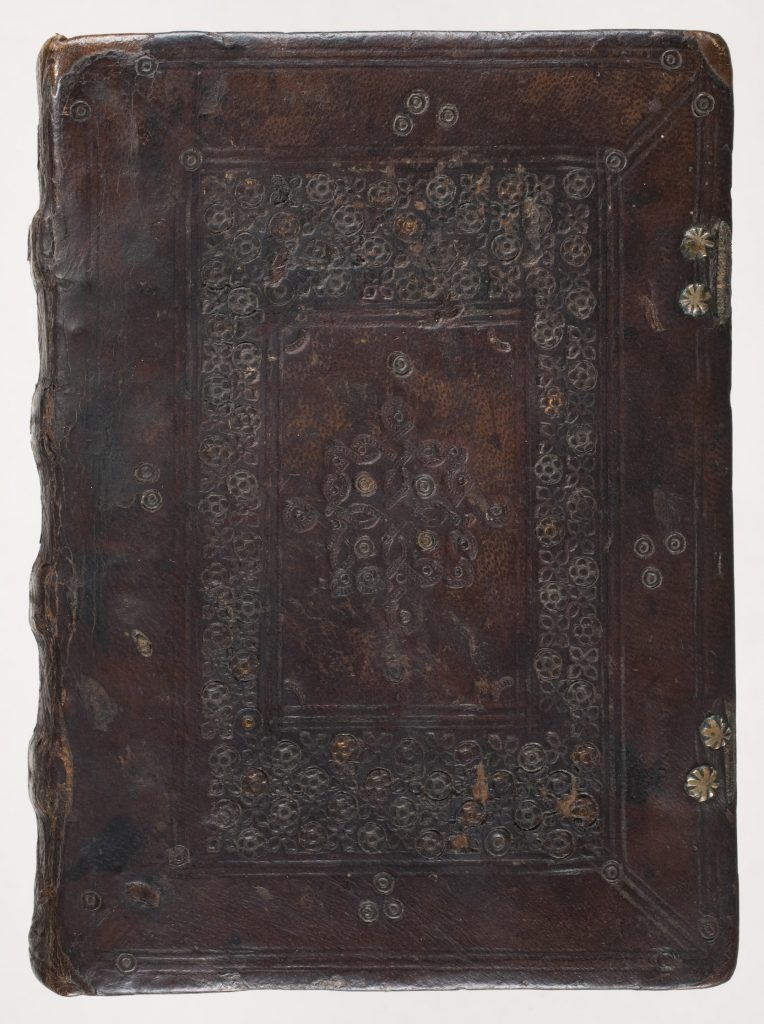

When Sallust first published his work it would have been written by hand on rolls made of papyrus as this was the normal form of a book in antiquity.[6] The copy held by the University Library however, is a codex, a small book of approximately 140 millimetres high by 100 millimetres wide, featuring a brown hard cover with decorative features. The codex itself is comprised of 110 vellum leaves or 220 pages. The text is written in a neat humanist script and where a new sentence begins at the start of a line a larger capital letter appears in the margin. The leaves have been grouped into quires, or ‘gatherings’, made up of ten leaves. The last page of each quire has a catchword at the bottom, which matches the first word of the following section. Occasionally the scribe has enclosed the catchword in what can be described as an ‘ornamental doodle’, some of which are quite elaborate.[7] The manuscript includes only a few examples of marginalia and minimal signs of wear suggesting that the book received little use until it was acquired by the University of Canterbury.

From Rome to Canterbury: A History of the Canterbury Sallust

The Canterbury Sallust has an interesting history in its own right, travelling across the world as it did from its original source in Europe to the University of Canterbury Library in New Zealand. Unfortunately, prior to its acquisition for the Library little is certain about the manuscript’s origins. What is known is that on 4 May 1953 the manuscript was sold at Sotheby’s to C. A. Stonehill, and several further sales followed in the next thirteen years before it was acquired by Professor of Classics D.A. Kidd for the University of Canterbury in 1966.

The manuscript likely originates from northeast Italy and has been dated to c. 1465-1470 CE. The binding shows similarities with texts from Ferrara and Cesena, and is influenced by the style associated with Florence. From Italy the manuscript appears to have moved to France. This is indicated on the front flyleaf where there is an erased signature, ‘Monchol’, which is believed to be of French sixteenth-century origin. Other names written in the manuscript suggest that it may have belonged to the family of Pierre de Monchal, an advocate at the parliament of Paris. His relative Charles de Monchal, the archbishop of Toulouse, was a renowned bibliophile and established a large library. It is possible that our manuscript was part of this library, but nothing is known for certain and little else is recorded until the mid-twentieth century.[8]

In 1966 Professor Kidd was in England on leave and it was hoped that while there he might purchase for the University Library a representative manuscript in Latin. Professor Kidd found however that due to an increase in sales to various institutions there were few manuscripts on the market and the prices of the remaining manuscripts were rising steadily.[9] It was fortunate that when the Sallust manuscript was located it was closely followed by the announcement of a bequest from Walter Cuthbert Colee.

Walter Colee (1876-1966) was a graduate of Canterbury College and a former headmaster of a number of Christchurch primary schools. Colee was active in the world of education, serving as a member of the Canterbury University College Council from 1934 to 1949, and holding the position of Chairman for two years. He also served on the Senate of the University of New Zealand and was a member of the Lincoln College Board of Governors for nineteen years. His bequest of £100 was gifted to the University Library with no limitations as to how the money should be spent. The Library was therefore free to spend the money to its best advantage. Rather than use the money for ordinary books the Library deemed it appropriate to purchase something special, “something beyond our ordinary means yet of use to some and of value for everyone.”[10] As Latin was one of Colee’s interests it seemed fitting that the first early manuscript in Latin acquired by the University should be a lasting memorial to his work.

Conclusion

The Canterbury Sallust has had a long history in its own right, travelling around the world from Italy to France and on to England, eventually making its way to New Zealand. When it was originally produced, the manuscript itself increased the understanding of the ancient Romans of their place in the world though its narrative of conquest. Texts such as Sallust’s Bellum Jugurthinum helped to educate Romans about the world beyond their own cities and foster an interest in the history and geography of the world in which they lived. Today the work of Sallust continues to be a valuable teaching tool, expanding the horizons of a new generation of students, as part of the University of Canterbury Library Rare Books Collection.

Emily Rosevear recently competed her Master’s Degree in History at the University of Canterbury and currently works as a Gallery Host at the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities.

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to Special Collections Librarian Damian Cairns and the University of Canterbury Macmillan Brown Library for their continued support, and permission to reproduce images for this article. All images are copyright to UC.

References

[1] Daniela Dueck and Kai Brodersen, Geography in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 3.

[2] Ibid., 4.

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] Ibid., 46.

[5] Garry Morrison, “The Canterbury Sallust” in Treasures of the University of Canterbury Library ed by Chris Jones, Bronwyn Matthews and Jennifer Clement (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2011), 90.

[6] D.A. Kidd, The Canterbury Sallust. (Christchurch: University of Canterbury, 1969).

[7] Morrison, “The Canterbury Sallust”, 92.

[8] Ibid, 92-93.

[9] C. W. Collins, ‘Foreword’, in The Canterbury Sallust, by D.A. Kidd (Christchurch: University of Canterbury, 1969).

[10] Ibid.

Beautifully written and intriguing article, thank you E,mily!