Roswyn Wiltshire continues her exploration of the challenges of researching ancient glass from the collection of Canterbury Museum. Here she probes the possible identification of some ‘un-Roman’ examples of glass.

It was a peculiar grey I had not seen in the glass I’d studied thus far. The roughly shorn top that had been identified as a stopper was in fact a solid part of the object, and from its shoulder it tapered inward to a cracked end. It was clearly not the Roman amphora it had been identified as in the database, but its true identity was a mystery to me. I was working on a catalogue of the Roman glass in the Canterbury Museum collection as part of my research for a Master’s of Art in Classics. As my research progressed, I encountered a number of pieces of glass that were decidedly ‘un-Roman’.

By the time I encountered the mystery grey vessel (EA1979.545) I had read quite a bit about ancient glass; French excavation reports and typologies on glass from the eastern Mediterranean, well-illustrated American catalogues and detailed German ones, British hand-books and the heavy tomes of the Lebanese excavations of an important Tyrian cemetery. But in all this reading I had not come across anything like the small object I now held.

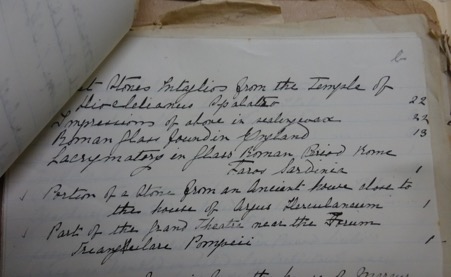

Fortunately I had a lead to follow: a sticker identified the piece as having formerly belonged to the Bateman Collection before coming to Canterbury Museum. Thomas Bateman (1821-1861), an English antiquarian and excavator of local burial mounds, had compiled a catalogue of the collection he displayed in his home [1]. From this I learned that my mystery glass had come from the “City excavations” of 1844. Excited to have found its provenance – the City of London – I neglected to read a line that would have instantly identified the object type, instead sending an inquiry to the Museum of London.

As it turns out I learned much more this way – I was swiftly put in touch with a curator who immediately recognised the description: a tazza or goblet stem of the late 16th to mid-17th century CE. She could even tell me the London street where they were produced in the 17th century. Leafing back through Bateman’s catalogue I saw that it had indeed been identified in the Early Modern [2] chapter as an ornamental goblet stem. This led to the question – how had it come to be listed as a Roman amphora in Canterbury Museum?

Unfortunately not all research questions are as easy to answer, but the next time a vessel struck me as odd I could now trust my instincts and browse texts on Early Modern glassware before toiling vainly through tomes on Roman glass. An extremely elongated bottle, greyish in its thick base, was another candidate for misidentification (EA1979.543). Sure enough, when I searched for 18th century CE pharmaceutical bottles, the first photo was a match.

More tricky was another excessively long bottle of a rather pretty aquamarine colour (EA1979.509). Here an excavation report creating a typology of pharmaceutical bottles excavated in London held the answer [3]. While my example did not resemble the illustrations in exact details, the general features, tell-tale colour, and the statement that standardisation was only in size, were enough to give a ca. 17th century CE date. From this report I could also confirm the identity of the other bottle (EA1979.543) as 18th, or even 19th century CE.

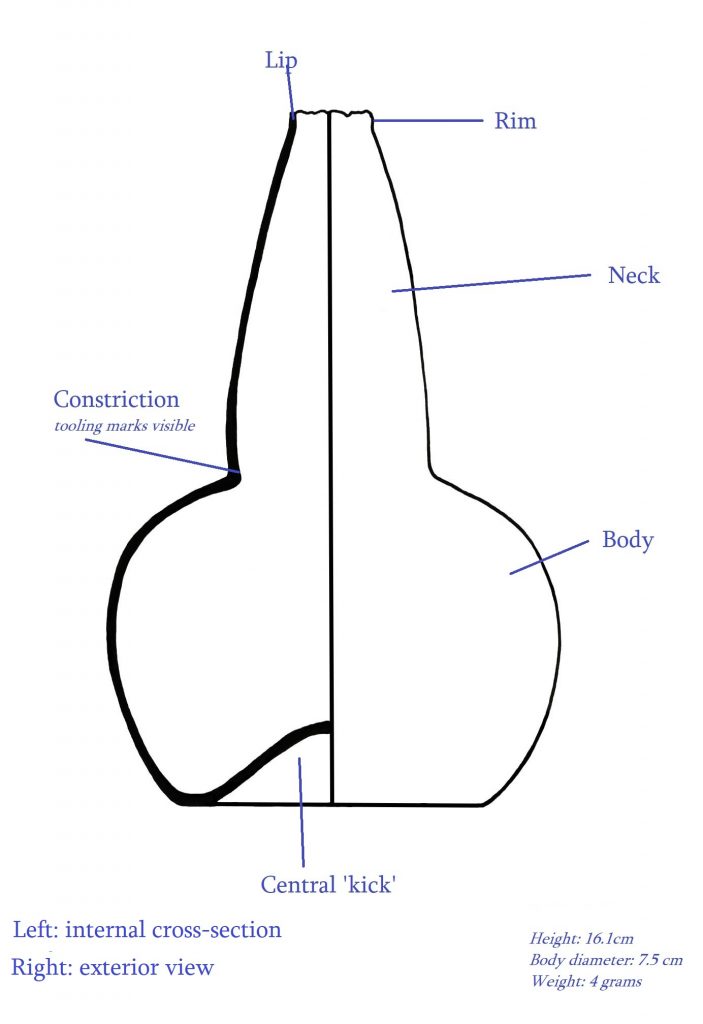

The final piece I believe has been mistaken for Roman glass was harder to place, and for want of expertise I will have to leave the formal identification of it to someone better versed in Early Modern glass from Europe. The bottle in question (EA1979.592) has features found on early modern liquor bottles – the almost globular body, the high kick [4], the neck bulging out before a notable constriction – but I did not find a close match. The top is carefully broken, with tiny rough edges, and below the rim is a crust of some dark material. It might be the remains of wax, used to seal bottles before corks became ubiquitous, but I will have to leave the final say on this to another expert.

I was left contemplating the nature of the journey these glass objects took to Canterbury Museum. They are not forgeries, items created with intent to deceive – all three vessels are genuine examples of Early Modern glass. The question therefore became are they fakes, items deliberately given a false identification, or had they just been the victims of honest mistaken identity? Some may have been misplaced in storage among ancient objects, but the 17th century apothecary bottle was certainly displayed in the Canterbury Museum Antiquity Room [5] among genuinely ancient vessels.

Perhaps there is a hint in a snippet from the Northampton Mercury in 1879 (Sunday the 4th of October) which informed readers that “many a bottle from the time of King Charles II, fished out of the river Thames, has been sold as old Roman glass”. At that same time, across the globe, Canterbury Museum was growing and expanding its collections through exchanges and bequests. It is possible that some of these bottles were the objects of such fraud, later becoming well-intentioned gifts to museums.

The experience of finding misidentified objects and re-dating them was a very useful one. Not only did I get the opportunity to broaden my skillset, but I also gained appreciation for the kinds of difficulties museums face. Now that the mistaken identity has been removed, others will be able to do further research into these vessels’ real identity. While this episode remains a story of their ongoing history, they can now move on from being ‘un-Roman’ to interesting artefacts in their own right!

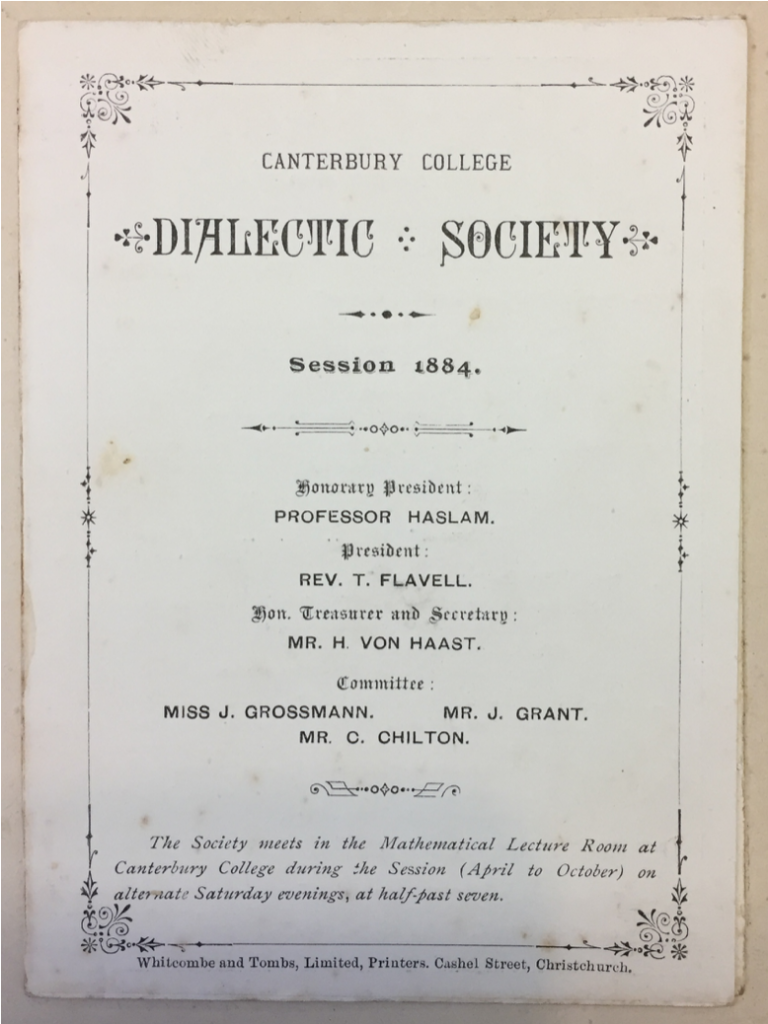

Roswyn Wiltshire has just completed a Master of Arts in Classics at the University of Canterbury, researching the hitherto unpublished collection of ancient glass in Canterbury Museum. She has worked with the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities since 2017.

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to the staff of Canterbury Museum for their generous support of this research project, and permission to reproduce images of the Roman glass for this article. Thanks also to photographer Matthew Walters, Science Communication and Digital Imaging, UC School of Biological Sciences, for producing such striking images of the glass.

Footnotes:

[1] Bateman, T. 1855. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities and Miscellaneous Objects Preserved in the Museum of Thomas Bateman, at Lomberdale House, Derbyshire. Blackwell: James Gratton.

[2] Early Modern glass dates to between ca. 1500–1800 CE

[3] Castillo Cardenas, K. 2014. ‘Pharmaceutical glass in Post-Medieval London: a Proposed typology’. 309-315 in London Archaeologist.

[4] A feature common on modern wine bottles: the base is pushed inward at the centre (see diagram).

[5] It can be deduced that this object was on display in the Antiquities Room because it was assigned an AR number (AR413.0).